by Allegra Goodman

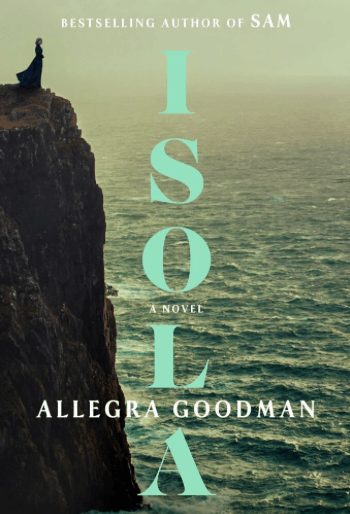

Allegra Goodman has written several novels. Her work has also appeared in The New Yorker and Best American Short Stories. In 2025 she published, Isola, a beautifully written, meticulously researched, and utterly compelling novel about Marguerite de Roberval.

Interview with Allegra Goodman, January 2026

LR: First, I want to congratulate you on this brilliant novel and the critical acclaim that it has received. As someone who researches sixteenth-century women, it was wonderful to see Isola featured in Reese’s Book Club and in the New York Times on their list of notable books, best historical fiction, and recommended survival stories of 2025.

LR: Over the centuries European and Canadian writers have composed different versions of Marguerite de Roberval’s story. Can you explain what compelled you to write a new version and how you knew that it would appeal to American readers today?

AG: I first encountered Marguerite in a children’s book about Canadian history that I’d checked out from the library to share with my own sons on a visit to Canada. The author wrote about Marguerite’s marooning in a quick aside during a discussion of Jacques Cartier’s third and final voyage to New France. As soon as I saw this brief mention of Marguerite, I was intrigued and wanted to know more. Over the course of several years, I began to read everything I could about this young noblewoman and her world. I believed that her story would be a fascinating subject for a historical novel, and I looked to see who else might have written about her. I discovered various novels for young readers, some poems, and some accounts of her as a castaway. These were mostly Canadian. I read the 2003 novel Elle by Canadian novelist Douglas Glover and enjoyed his experimental / magical realist take on her story. I also knew that my version would be different in style and substance. From the beginning I imagined writing Marguerite’s story in the realist tradition of castaway tales I’d loved as child—Robinson Crusoe, Island of the Blue Dolphins, Kidnapped. I saw my version as an adventure story—a tale of resilience, grounded in the practicalities of survival on an island, and as a tale of spiritual discovery in which a young woman travels to a place as distant and strange to her as the moon.

LR: Elizabeth Boyer has discussed a “conspiracy of silence” surrounding Marguerite de Roberval’s harrowing experience. Given the paucity of archival documents, could you share some of the challenges and successes that you encountered while doing historical research for this work?

The early modern accounts of Marguerite de Roberval’s story are all quite brief. Can you discuss the process of expanding the story and developing the complexity of the characters in your impressive novel?

AG: The gaps that challenge a historian provide opportunities for a novelist. As you know, the two contemporary accounts of Marguerite’s ordeal are only a few pages each. They also conflict with each other. This meant that I had to choose which events and details to use. The Queen of Navarre’s account turns Marguerite’s story into a fable about a faithful wife choosing to share her husband’s punishment. Andre Thevet’s account focuses on the supernatural with his emphasis on the demonic voices Marguerite hears while alone on the island. I used what I could from the Queen and Thevet. I paid attention when they concurred on certain details such as Marguerite’s use of arquebuses and her battles against white bears. However, I needed to conjure up much more.

As a novelist, I was interested in developing the arc of Marguerite’s journey from France to the New World and back. The novel is a genre that supports detail, nuance, and complexity and allows for development. The novel is capacious. I had the length of a book to show how Marguerite comes into her own.

Because I had so little to go on, I supplemented contemporary accounts with research of my own. I studied the climate in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and the flora and fauna of the islands there. I researched the way that polar bears hunt. I researched ships of the period both in books and in person. In London I walked on the replica of the Golden Hind, in order to understand the scale of the ship, the way it was constructed, and how each level connected to the one below. The early Italian map of the area which is reproduced in the first pages of my book proved inspiring to me. This map reveals that nothing was known about the interior of Canada. The blank space there frightens Marguerite.

I read as much as I could about the historical figures in my book, particularly the Queen of Navarre. (I would have read your book, but it had not been published yet!) I was interested in the queen’s sympathy for Catholic reformers, and her role as patron of the arts. After learning as much as I could, I tried to imagine what the queen might have said to Marguerite if she had met her.

The queen says in her account that Marguerite ended up teaching young ladies. I extrapolated from this that Marguerite might have begun a school of her own with a royal license. I did a lot of research on convent schools of the period and was fascinated by the way nuns and lay teachers taught poor as well as rich girls. Of course, much of my research did not end up in my book. Because I was writing a novel, my allegiance was to Marguerite’s story, and I could not take the reader down every rabbit hole.

When I read about Cartier’s third voyage, I was fascinated by his decision to flout Roberval and return home. Historians believe that he cut the ropes of his ships and slipped away in the night, and as soon as I saw that I knew I wanted to dramatize that episode and weave it into the drama on Roberval’s ship.

Paintings proved valuable to me. I was particularly interested in paintings of young ladies at chess or playing the virginal. I studied those by Sofonisba Anguissola. I also studied the famous painting of Marguerite of Navarre and used it for my description of the queen in her dark gown adorned with a jeweled cross. Elsewhere, I mention her bright green bird.

I listened to lute music from the time and looked at period instruments in museums and in photographs. My descriptions of the virginals with their inscriptions are based on surviving instruments. In museums and in books I studied jewelry, furniture, objects, and interiors of the period. Roberval’s cabinet is based on an ebony and ivory cabinet in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As for Roberval, I learned the events of his life but extrapolated to imagine his relationship with Marguerite, and his treatment of her. I felt certain that Roberval was a crypto-Protestant and endowed him with strict Calvinist beliefs. In my book he is a cruel and avaricious guardian but also a gifted musician and energetic commander. He is both religious and worldly.

Thevet mentions that Marguerite had a servant called Damienne and I took her name for my book, but as with Roberval, I imagined Damienne’s character and wrote her as a faithful nurse. Marguerite’s teacher Madame D’Artois and her daughter Claire are my inventions, and I imagined Madame D’Artois’ friendship with Clement Marot, a real poet.

As you can see, I used the scant historical record as a jumping off point.

LR: As a specialist in medieval and early modern literature, I was delighted to see references to Christine de Pizan, Anne de France, and Clément Marot. I especially appreciated the vivid exchange between Marguerite de Roberval and Marguerite de Navarre in Isola. Can you explain why you chose to highlight these specific writers?

AG: When I began researching Isola I looked for women’s voices. Early on, I discovered Anne de France and her Lessons, a kind of guidebook for being a good princess or noblewoman. Anne emphasizes that a proper lady is modest, gracious, chaste, and careful. She does not speak out of turn or take any initiative on her own. She is kind to her servants but never too familiar. She certainly will never speak to a man alone. If her husband dies, she does not weep or wail or make foolish oaths. She accepts the loss and does her duty. Above all, the proper noblewoman remembers that one day she will die, her wretched body will decay, and her soul will stand in judgement. Reading all the Lessons, I realized of course that Anne knew of cases where ladies indulged in the shocking behavior she warns against. I decided that I would begin each section of my novel with an excerpt, and that in each instance, whatever Anne advises, Marguerite would do the opposite, either by choice or by necessity. I wanted the reader to understand the cultural framework of Marguerite’s world and the ideal behavior of a woman. Then the reader could have a baseline to gauge the distance Marguerite travels.

Also, early in my research I began reading Marguerite de Navarre and of course I studied her Heptameron—not just for the queen’s account of Marguerite’s adventure, but to see how this story fit with others in the collection. I was struck by the queen’s moralistic tone and at the same time by her worldliness. Many of her stories are racy and novelistic. I could see that the queen fancied herself a moralist but also a raconteur entertaining as well as teaching others with her tales. I try to capture the queen’s sense of authorship when Marguerite meets her in my book. Here I was inspired in part by the moment in Homer when Odysseus on his long journey home attends a feast where poets sing of Troy. Odysseus weeps to hear others recount events he lived, witnessed, and endured. Imagining Marguerite as a hero returning from an epic journey, I wondered how she might respond to those who tell her story. How Roberval might undermine her. How Marguerite might react with recognition or even indignation to the queen’s account. How Marguerite might hope for favor and risk the queen’s anger and ultimately turn a tricky situation to her advantage.

I include Christine de Pizan as a counterpoint to Anne of France. Anne advises her daughter on proper behavior, so that she will live beyond reproach. Her Lessons caution young ladies to stay in their lane. Christine’s project is quite different. Her Book of the City of the Ladies defends women against what she sees as slander against their sex. While Anne warns against weakness and temptation, Christine praises women for their rationality, wisdom, and faithfulness. Anne wants women to guard against their own weakness. Christine wants women to know their own strength and so she provides a detailed list of heroic women and their deeds. I imagined Marguerite’s learned teacher Madame D’Artois teaching from Christine’s book of great women, biblical, classical and contemporary. These are not simply courtly ladies but heroines who hunt and go to battle and survive great hardship—as Marguerite will do later.

LR: In your opinion, which passage in Isola most clearly represents the indomitable spirit of Marguerite de Roberval?

AG: If I had to choose one passage it would be Marguerite’s retort to Roberval at the end of the book where she confronts him and says there is nothing else he can do to hurt her.

“Would you turn me out? I can sleep upon the ground. Would you starve me? I know how to hunt. Would you break my heart? You have done it— and I do not have another heart to break. There is nothing more that you can do to me. I will not listen.” (p. 388)

These were satisfying words to write, because they are not hyperbole. By this time the reader knows what Marguerite has endured. She’s earned her strength.

LR: Which aspects of Marguerite de Roberval’s story do you want your readers to take away from Isola?

AG: It’s not so much that I want readers to take something from Marguerite’s story. It’s that I want them to journey with her, to feel what she does on her island, to reflect as she does on what it is like to be alone. To wonder with her if there’s a reason to keep on fighting to survive, to struggle with her, to grieve and to rejoice with her—and to see the world differently as she does when she returns.